In modern feed formulation, we tend to pay close attention to energy, proteins, and synthetic amino acids. However, the physiological functioning of the animal depends critically on another group of nutrients that, despite not providing energy, are absolutely essential for the metabolism to function accurately: macrominerals. Their influence is not limited to bone structure or maintaining acid-base balance; they also determine the efficiency with which the animal uses the rest of the nutrients and, consequently, its productive performance.

Among macrominerals, four stand out for their direct impact on growth, health, and efficiency: calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), and sodium (Na). Their nutritional importance has been demonstrated for decades, and authors such as Ammerman, Baker, Henry, and Hall have insisted that it is not enough to meet theoretical requirements. The quality of mineral sources, their solubility, purity, particle size, and stability determine their true availability and, therefore, the animal's response.

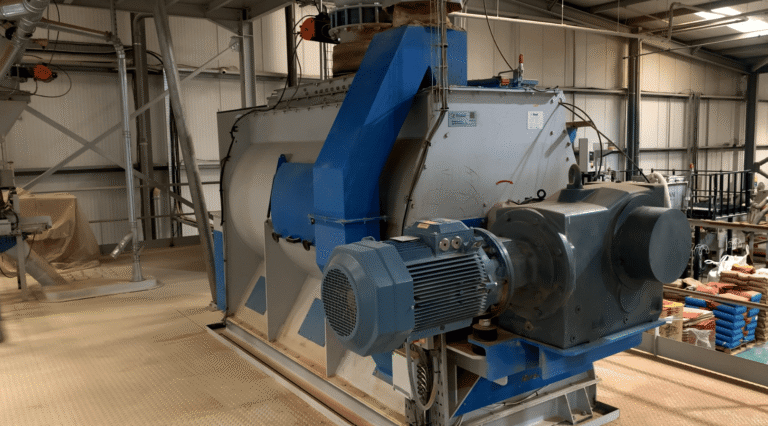

Furthermore, in a modern feed mill, macrominerals should not only be considered from a nutritional point of view. Their physical behavior—flowability, hygroscopicity, density, particle size—directly affects industrial processes such as dosing, mixing, internal transport, and unloading into hoppers. Understanding how each mineral behaves improves process reliability and consistency between batches.

This article provides an up-to-date technical overview of the role of these macrominerals, integrating physiological and industrial aspects, and drawing on classic references in nutrition and the practical experience of feed mills.

Calcium: much more than a structural component

Calcium is perhaps the macromineral most closely associated with bone structure, but its function is much broader. It is involved in muscle contraction, nerve transmission, blood clotting, and the activation of numerous enzymes. Insufficient or unbalanced calcium intake directly affects skeletal development, animal welfare, and production efficiency.

Sources of calcium and industrial variability

The most common sources of calcium in animal feed are:

- Calcium carbonate

- Calcium phosphates (dicalcium, monodicalcium, monocalcium)

- Animal meal (increasingly less used)

Calcium carbonate is the predominant source due to its availability and cost, but its quality is surprisingly variable. Roland and Bryant have already demonstrated that two carbonates that appear similar can have very different solubilities depending on their mineral purity, particle size, and heat treatment.

From an industrial perspective, the particle size of calcium carbonate directly affects its behavior in hoppers and dosing systems. Particles that are too fine tend to generate dust, caking, and bridging in hoppers; coarse particles can segregate from the rest of the ingredients during internal transport. The design of the factory—especially the geometry of the hoppers and the capacity of the mixer—has a significant influence on the handling of this mineral.

The role of particle size

Particle size is critical for both physiological absorption and industrial performance. In poultry, coarse calcium carbonate is retained longer in the gizzard, providing a sustained supply that improves shell quality. In swine, fine particles are more soluble, but can interact with phosphorus and reduce phytase efficacy if stomach pH is inadequate.

Interactions of calcium with other nutrients

Calcium interacts with phytates, phosphates, and amino acids. An excess can decrease phosphorus availability and limit the effectiveness of phytases. Likewise, very high levels alter the digestibility of essential amino acids, increase fecal excretion, and worsen feed conversion. From an environmental standpoint, an excess of calcium combined with unabsorbed phosphorus increases mineral losses.

Phosphorus: the most expensive and variable mineral

Phosphorus participates in fundamental processes: bone formation, energy metabolism (ATP), phosphorylation, nutrient transport, and cell regulation. It is one of the most expensive minerals in the diet and also one of the most affected by variability between batches.

Variability in phosphorus sources

The most common sources are:

- Cereal phytates (low availability)

- Inorganic phosphates (DCP, MDCP, MCP)

- Animal meal

- Vegetable by-products

The work of Hall (1997) and the CVB (1997) showed that phosphorus digestibility can vary by more than 20% even within the same type of phosphate. This directly affects formulation and requires working with safety margins or analytically characterizing each supply.

Fitase: keys to its effectiveness

The incorporation of phytases revolutionized mineral nutrition, allowing the release of phosphorus bound to phytates and reducing the use of inorganic phosphates. However, their effectiveness depends on parameters such as:

- pH of the gastrointestinal tract

- calcium level

- type of phytate present in food

- retention time

From an industrial standpoint, the actual action of phytase also depends on how evenly it is distributed within the feed. Poor mixing, especially in facilities with large-capacity mixers, can significantly reduce its effectiveness.

Magnesium: an essential mineral

Although less talked about than calcium or phosphorus, magnesium is involved in more than 300 enzymatic reactions. It is essential for energy metabolism, neuromuscular stability, muscle relaxation, and skeletal integrity.

Sources of magnesium and variability

The most commonly used sources are:

- Magnesium oxide

- Magnesium carbonate

- Magnesium sulfate

Magnesium oxide stands out for its concentration, but its actual solubility varies greatly depending on its origin, calcination process, and manufacturing temperature. Henry (1995) emphasized that two oxides with similar chemical content can have radically different practical availability.

In feed mills, low-solubility oxides can behave like very dense particles that segregate easily during mixing, especially in plants with long transport routes or multiple drop points.

Magnesium in stressful situations

Magnesium modulates muscle excitability. In situations of thermal or metabolic stress, small deficiencies can cause muscle tremors, poorer conversion, lower consumption, and reduced growth. On farms in hot climates, its role is particularly important.

Sodium: water balance and active transport

Sodium participates in nerve transmission, acid-base regulation, osmotic balance, and active nutrient transport. Its intake directly influences water intake and intestinal physiology.

Sodium sources

- Sodium chloride (common salt)

- Sodium bicarbonate

Salt provides sodium and chloride; bicarbonate introduces a buffering effect, which is essential in acidogenic diets or in conditions of high heat. Baker (1995) emphasized that it is not sodium alone, but rather the electrolyte balance (Na + K – Cl) that determines many metabolic processes.

The industrial quality of minerals

The actual quality of minerals does not depend solely on their chemical composition. Their behavior within the factory influences fluidity, dosing, falling speed, mixing, and homogeneity. The most critical aspects are:

- Particle size distribution

- Bulk density

- Hygroscopicity

- Physical-chemical stability

- Compatibility with vitamins and enzymes

Very fine minerals generate dust, caking, and the risk of retention on hopper walls. Very dense minerals tend to segregate during transport or mixing. Hygroscopic minerals can absorb moisture in silos, compact, and form crusts that make discharge difficult.

For a modern factory equipped with automatic dosing systems, poor flow can result in weighing errors, irregular drops, and variability between batches. The design of the hoppers, the angles of repose, the type of gates, and the mixer play a fundamental role.

Particle size determines both the solubility of the mineral and its behavior in hoppers, feeders, and mixers. The following chart summarizes this relationship and explains why choosing the right particle size is essential in nutrition and industrial processing.

| Particle type | Solubility | Stability in mixture |

|---|---|---|

| Fine particle | High | Average |

| Average particle | Optimal | Optimal |

| Coarse particle | Low | Variable* |

* Stability depends on the type of mixer, mixing time, and subsequent transport within the factory.

Macrominerals and industrial mixing

Mixing is one of the most decisive processes for the final uniformity of the feed. In large-capacity factories, where the mixers must operate at high speeds, minerals with very different particle sizes generate segregation patterns. This is exacerbated during subsequent transport in screw conveyors or elevators, where the denser fractions tend to migrate.

A high-quality premix allows all these minerals to be introduced in the form of a single homogeneous ingredient, reducing variability between batches and improving the coefficient of variation of the mixture. Plants that operate with automated systems benefit greatly from this uniformity, as it reduces dosing errors and the need to redo batches.

Macrominerals in premixes: nutritional and technological advantages

The classical literature (Henry, 1995; Ammerman et al., 1995) highlights that the minerals included in premixes offer benefits from both a nutritional and technological standpoint:

- Better homogeneity even at low inclusions

- Lower risk of degradation of sensitive vitamins

- Dust and clumping reduction

- Improved fluidity in dosing

- Reduction in human error

From a process perspective, a well-manufactured premix behaves like a stable and manageable ingredient. This facilitates dosing from the macro-ingredient hopper, reduces weighing problems, and improves batch traceability.

Conclusion: the indispensable role of macrominerals

Calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and sodium are fundamental pillars of animal nutrition. Their functions range from energy metabolism and neuromuscular transmission to skeletal integrity and acid-base regulation. But their importance is not limited to physiology. In a modern feed mill, minerals are materials with their own physical behaviors that can facilitate or hinder the industrial process.

The actual quality of minerals—solubility, particle size, density, compatibility—directly affects dosing, mixing, and homogeneity. Understanding these factors allows for more accurate formulation, reduced costs, optimized machinery efficiency, and stable production.

The work of Ammerman, Baker, Henry, Hall, and the CVB continues to be a reference for understanding the complexity of these minerals. Integrating this knowledge into the engineering and design of feed mills allows for more robust processes, more homogeneous products, and nutrition that is better tailored to the actual needs of the animal.

References

- Ammerman, C.B., Baker, D.H., & Lewis, A.J. (1995). Bioavailability of Nutrients for Animals: Amino Acids, Minerals, and Vitamins. Academic Press.

- Baker, D. (1995). Nutrient Requirements and Responses. In: Bioavailability of Nutrients for Animals. Academic Press.

- CVB (1997). Documentation Report 27: Digestibility and Availability of Phosphorus in Feed Ingredients. Central Feed Agency, Netherlands.

- Hall, L.E. (1997). Variation in Phosphorus Digestibility of Feed Ingredients. Journal of Applied Poultry Research.

- Henry, P.R. (1995). Magnesium and Trace Mineral Bioavailability. In: Bioavailability of Nutrients for Animals. Academic Press.

- Roland, D.A., & Bryant, M.M. (1994). Particle Size and Calcium Utilization in Laying Hens. Poultry Science.