In the feed manufacturing industry, the coefficient of variation in the mixing process has become an almost automatic benchmark for assessing the quality of a mixture. It is cited in audits, used to validate equipment, and in many cases, employed as the definitive argument for accepting or rejecting a facility. However, the reality on the ground shows that this indicator alone tells us less than it seems.

The problem is not the coefficient of variation itself, but rather how it is interpreted. Reducing the quality of the mixture to a single numerical value, without analyzing how it was obtained or what variables were involved, often leads to erroneous conclusions and, frequently, to poor technical decisions.

A resume is a useful tool, but only when you understand its scope and, above all, its limitations.

What does the coefficient of variation measure?

From a statistical point of view, the coefficient of variation expresses the dispersion of a component within a mixture in relation to its mean value. In practical terms, it allows us to know to what extent the different points in the mixture contain similar proportions of a given ingredient.

In industrial practice, ranges have been established that serve as a reference. Values below 5 % are usually associated with highly homogeneous mixtures; values between 5 % and 10 % are considered acceptable; above that threshold, problems begin to arise that require a review of the process. These ranges, widely used in the sector, are useful as a guide, but cannot be analyzed in isolation.

A low CV does not guarantee, on its own, that the mixture will be correct in all subsequent stages of the process. Similarly, a slightly higher CV does not always imply a mixer failure. The key is to understand what has caused this result.

The CV as the result of a system, not a machine

One of the most common mistakes in the plant is to directly attribute the value of the mixing coefficient of variation to the mixing equipment. In reality, the CV is the end result of a complete system involving multiple variables.

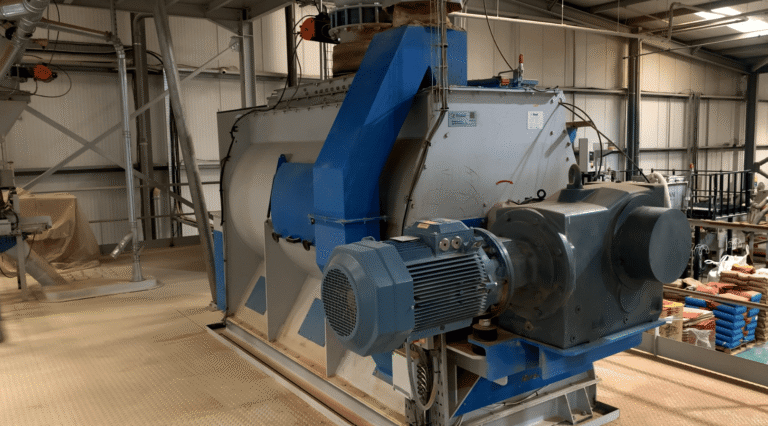

The design of the mixer is undoubtedly a determining factor. The type of equipment, the geometry of the rotor, the ratio between the length and diameter of the tank, and the actual useful capacity directly influence the dynamics of the product during mixing. Two mixers with the same nominal volume can behave very differently if their internal design is not comparable.

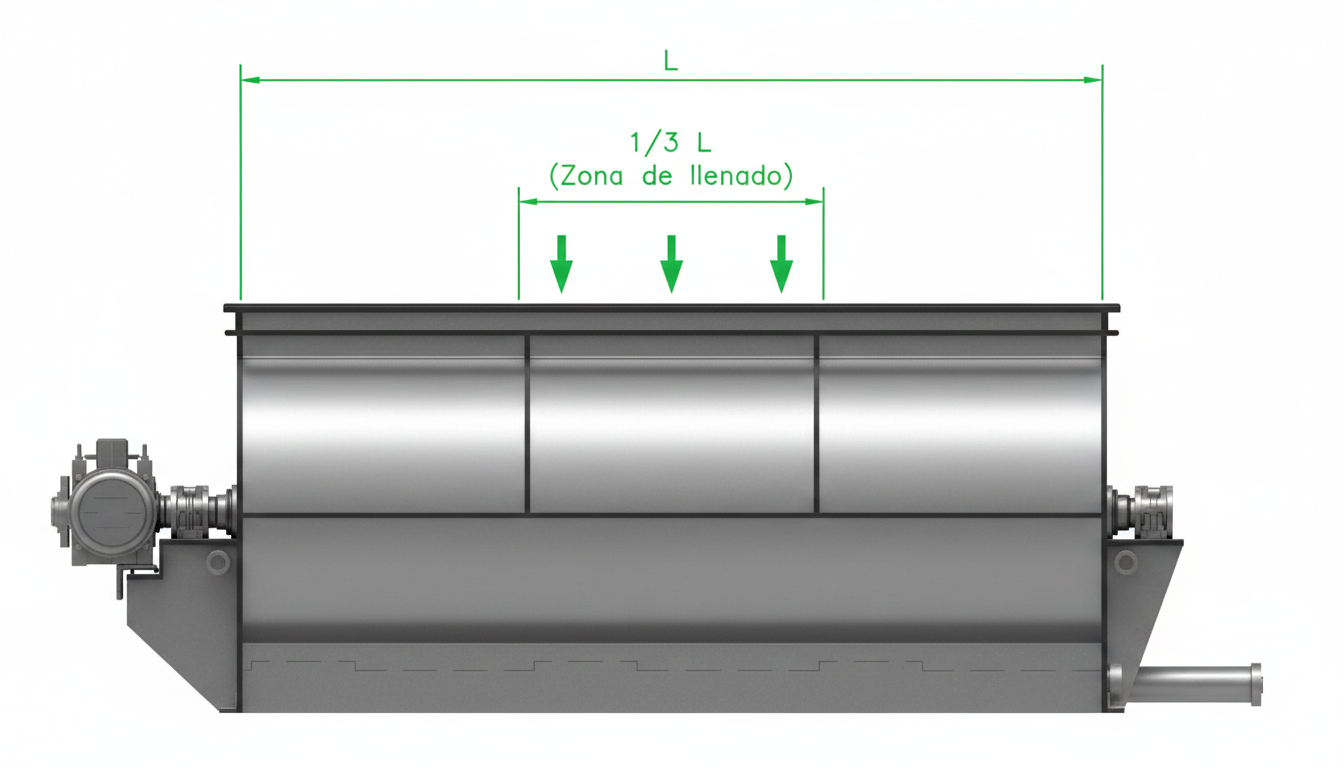

Added to this is the filling method. The initial distribution of the ingredients determines the entire subsequent process. When the product enters off-center or excessively concentrated in one spot, areas of accumulation are created that the rotor cannot always compensate for, no matter how long the mixing time is extended. In horizontal mixers, experience in the plant shows that a load distributed preferably in the central third of the length of the tank favors a faster internal flow regime. This type of filling reduces the formation of initial dead zones and allows the rotor to generate the axial and radial movements necessary for a homogeneous mixture sooner.

Time, precisely, is another of the great misunderstandings. There is a belief that increasing mixing time automatically improves homogeneity. In practice, once the optimum point has been reached, prolonging the cycle usually results in higher energy consumption and, in some cases, the onset of segregation, especially when there are significant differences in density or particle size.

The critical role of product characteristics

Not all formulas behave the same way in the mixer, and this is a fact that is often overlooked. The density of the ingredients, their particle size, moisture content, or the presence of liquids directly influence the final result.

Mixtures composed of components with similar densities tend to homogenize more easily. Conversely, when very disparate ingredients are combined, the risk of segregation increases, both during mixing and unloading.

Particle size plays a similar role. Significant differences in particle size hinder the stability of the mixture, even when the initial CV is correct. Added to this are factors such as humidity and viscosity, which are particularly relevant in formulas with added liquids. Poorly distributed dosing can quickly deteriorate the homogeneity obtained.

Even static electricity, under certain conditions, can cause internal adhesions that affect product performance and distort sampling results.

| Product parameter | Favorable condition | Unfavorable condition | Impact on the CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density of ingredients | Similar densities between components | Large differences in density | Lower dispersion and lower CV |

| Particle size distribution | Homogeneous particle size | Marked differences in size | Increased risk of segregation |

| Density–size relationship | Coherent (larger particles lighter or smaller particles denser) | Incoherent | CV instability |

| Distribution of fines | Controlled | Excess fines or dust | High CV variability |

| Behavior during discharge | Uniform flow | Separation by layers | Initial CV correct but not stable |

| Repeatability between batches | High | Low | Difficulty in validating the process |

The order in which the ingredients are added

In addition to the physical characteristics of each component, the order in which the ingredients are added to the mixer has a direct influence on the final homogeneity of the mixture. The same set of raw materials can result in very different coefficients of variation if the loading process is not correctly defined.

In industrial practice, macro-ingredients form the basis of the mixture and must be incorporated first. These components, usually cereal flours, account for most of the volume and create a matrix on which the rest of the ingredients are distributed.

Once the macro-ingredients have been loaded, minerals and correctors are added, which tend to have higher densities. Incorporating them into an already formed base facilitates their dispersion and reduces the risk of localized accumulations.

Additives, micro-ingredients, and medicated products should be incorporated at a later stage, when the mixture already has a certain degree of homogeneity. Adding them too early or without a sufficient base significantly increases the risk of variability in CV.

Finally, the addition of liquids—oils, fats, amino acids, or water—must be carried out in a controlled manner and, preferably, using spray systems. Uneven distribution of liquids not only affects the coefficient of variation, but can also alter the rheological behavior of the product and promote subsequent segregation.

Defining and adhering to a consistent incorporation order reduces the mixing time required, improves process repeatability, and yields more stable CV values between batches.

Measuring correctly is as important as mixing correctly.

When analyzing the coefficient of variation in mixing, it is essential to distinguish between a real problem in the process and an error in the way homogeneity is measured. A significant proportion of coefficients of variation considered “bad” do not originate in the mixing process, but in incorrect measurement. The marker used to evaluate homogeneity is decisive.

In industrial practice, microtracers and certain trace elements provide reliable results because they are distributed representatively throughout the mixture. In contrast, parameters such as protein, calcium, or vitamins are not suitable for this type of analysis. Using them often leads to misleading values, either because of their own variability or because of their physical behavior during the process.

Sampling is another critical point. Taking too few samples, concentrating them at a single point in time, or always extracting them from the same point invalidates any subsequent analysis. A correct protocol involves multiple samples, well distributed over time and taken at the mixer discharge or in the associated transport system.

Without rigorous sampling, the CV loses its value as a technical indicator.

| Appearance | Incorrect sampling | Correct sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | Very few samples (usually 2–3) | Minimum 8, usually 10 samples |

| Sampling time | Taken in a single moment | Taken at regular intervals |

| Point of intake | Always at the same point | Throughout the unloading or extraction transport |

| Representativeness of the batch | Partial and biased | Representative of the entire lot |

| Sensitivity to segregation | Very high | Controlled and minimized |

| CV value obtained | Misleading or not easily repeatable | Reliable and repeatable |

| Interpretation of the process | Incorrect conclusions about mixer performance | Correct diagnosis of mixture quality |

When a very low CV is truly significant

Under controlled conditions, it is possible to achieve coefficients of variation below 5%. However, these types of results are only truly significant when certain conditions are met: a correctly sized mixer, filling close to its useful capacity, ingredients with compatible physical characteristics, and a stable and repeatable process.

Seeking these values in complex formulas, with a high proportion of micro-ingredients or large differences in density, often leads to unrealistic expectations. In these cases, a slightly higher but stable and repeatable CV may be technically more valuable than an exceptional one-off result.

Operating characteristics of propeller mixers

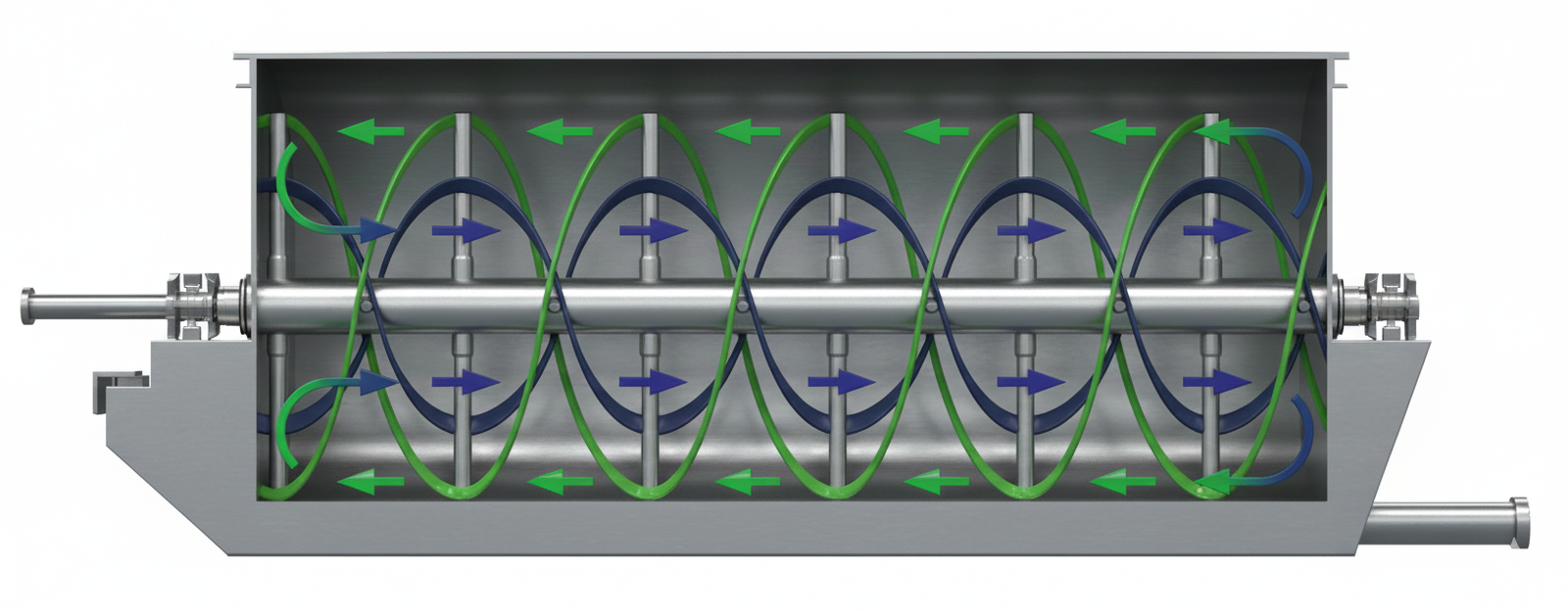

The horizontal propeller mixers They are characterized by a design aimed at generating a continuous and controlled flow of the product inside the tank. Unlike other systems, the double helix rotor drives the material both axially and radially, promoting constant redistribution of the components throughout the entire useful volume.

This type of design allows working with high filling levels, normally between 80% and 100% of the useful capacity, without compromising the quality of the mixture. Under these conditions, the energy applied is transmitted more evenly to the product, which contributes to low and, above all, stable coefficients of variation.

Another important feature is the ability to integrate the addition of liquids in a controlled manner. When injection is performed correctly, propeller mixers allow small amounts of liquids to be incorporated without causing agglomeration or over-moistened areas, maintaining the regularity of the process.

From an operational standpoint, mixing times are usually moderate, allowing for a good balance between productivity, energy consumption, and final homogeneity. This behavior makes propeller mixers particularly suitable for processes that require repeatability and continuous quality control.

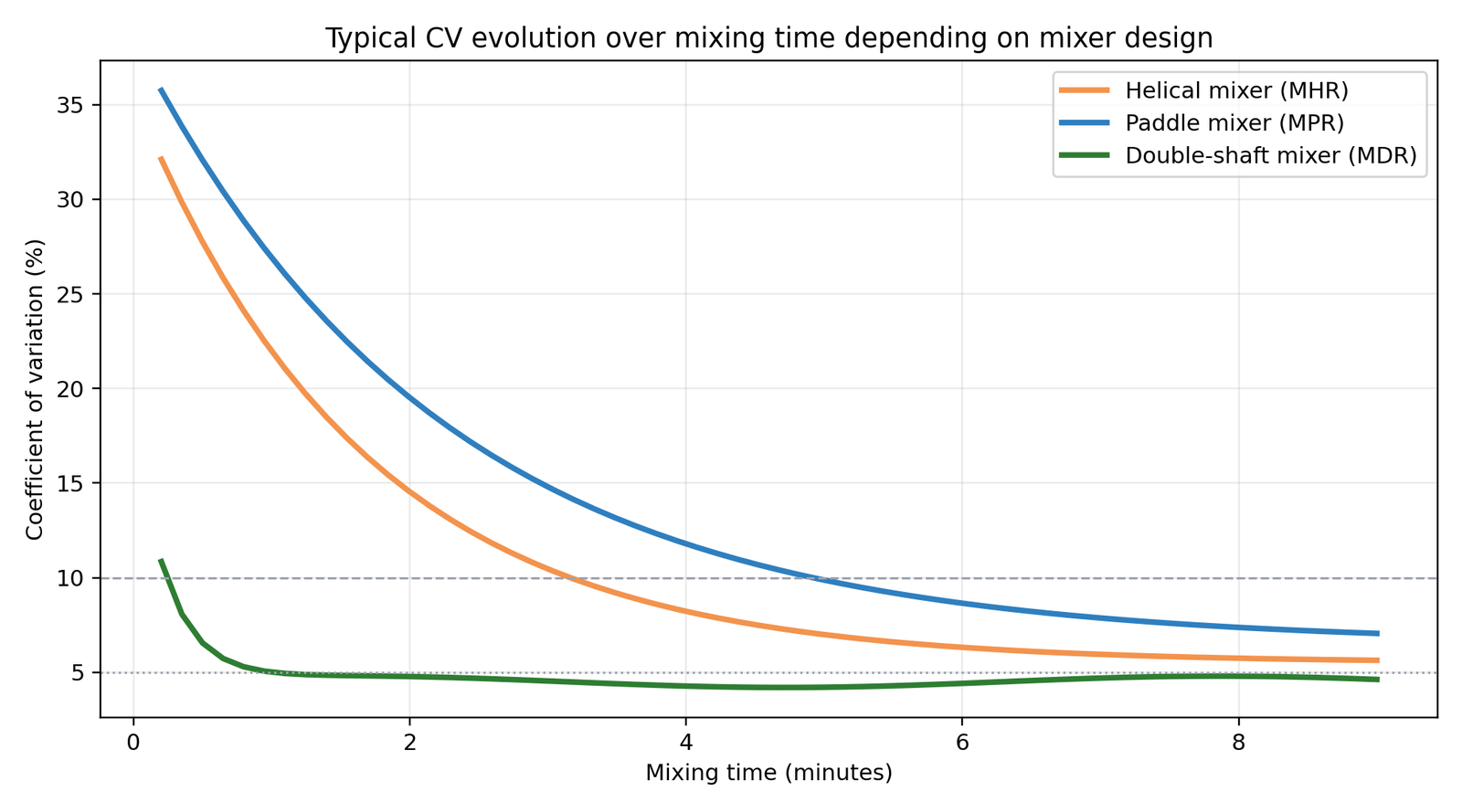

The evolution of the coefficient of variation according to the type of mixer

Analyzing the coefficient of variation in the mixing process solely as a final value can lead to incomplete interpretations of the mixing process. In industrial practice, it is much more revealing to observe how the CV evolves over time and how this evolution depends on the design of the mixer.

The different types of mixers exhibit clearly differentiated behaviors. In the case of twin-shaft mixers, the initial intensity of mixing causes a very rapid reduction in the coefficient of variation in the early stages of the cycle. This type of equipment reaches low CV values in a very short time, which can be advantageous in certain applications. However, once that point is reached, the curve tends to stabilize quickly, with limited room for improvement and greater sensitivity to variations in filling or formulation.

In the double-paddle or double-shaft mixers, the coefficient of variation experiences a very sharp reduction in the early stages of the mixing cycle. The high intensity of the movement generated by the two counter-rotating shafts causes a rapid redistribution of the ingredients, allowing low CV values to be achieved in a very short time. This behavior is particularly effective when rapid homogenization is required or when the process imposes very limited mixing times. However, once this initial level of homogeneity has been achieved, further improvement in CV is usually more limited, and the final result may show greater sensitivity to variations in filling, formulation, or the order in which ingredients are added.

Propeller mixers exhibit different behavior. The reduction in the coefficient of variation is more gradual, but also more consistent. As the mixing time progresses, the CV decreases continuously until it reaches stable and reproducible values. This type of evolution reflects a balance between mixing intensity and control of the internal flow of the product, which translates into good final homogeneity and, above all, greater process stability between batches.

In the paddle mixers, the decrease in the coefficient of variation is usually slower. Although acceptable values can be achieved, the time required to do so is longer and the final CV tends to be higher than that obtained with other designs. This behavior is particularly noticeable in formulations with significant differences in density or particle size, where the mixing mechanism based on pushing and turning is less efficient.

The comparison between the curves highlights a fundamental aspect: not all mixers reduce CV in the same way or with the same stability. While some technologies prioritize rapid initial reduction, others offer a more controlled and sustained decrease over time. From a process perspective, this stability is key, as a slightly higher but repeatable CV is often preferable to a very low value obtained on a one-off basis.

For this reason, the choice of a mixer should not be based solely on the minimum achievable coefficient of variation, but on the shape of the entire curve, its stabilization point, and its behavior in response to normal operating variations. Understanding this evolution allows for the correct adjustment of mixing times, optimization of energy consumption, and assurance of consistent homogeneity in production.

Conclusion

The coefficient of variation in mixing should not be understood as an end in itself, but rather as a diagnostic tool within a broader process. Good mixing does not end when a certain statistical value is reached. Unloading, subsequent transport, and integration with the rest of the line all influence the final quality of the product.

When analyzed using technical criteria, the coefficient of variation allows deviations to be detected, process times to be optimized, and the design of the installation to be adjusted. When used in a simplified manner, it runs the risk of becoming a meaningless number.